The Vibrance of Vinegar: Methods to Make Vinegar From Scratch

Homemade vinegar is a delicious ingredient in many foods and drinks: quick pickles, soups, sauces, salad dressings, desserts, jams, and more. Before we work on creating these recipes, it’s essential to understand the fundamentals of vinegar and how to make it from home.

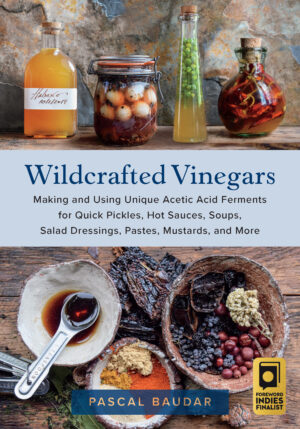

The following is an excerpt from Wildcrafted Vinegars by Pascal Baudar. It has been adapted for the web.

Unless otherwise noted, all photographs copyright © 2022 by Pascal Baudar.

Making Vinegar At Home

When I started looking at traditional food preservation techniques, which was before the internet and search engines were popular, making your own vinegar at home was a big mystery.

It seemed that you had to have special connections to people who had some sort of bacteria culture they called a mother, and those people were probably part of a shady, cultish fermentation society that kept its location and practice a secret.

This must have been the case, as I could not find anyone around me with information, and so I kept buying vinegar from the grocery store. It wasn’t until I started making my own wines and beers that I finally understood that fermentation was a simple, natural process. Well, sort of…

From Wine to Vinegar: Open Fermentation

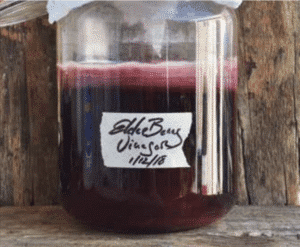

I had a friend who gifted me some elderberry wine every year, and it would always turn into vinegar within a couple of weeks.

It was a big mystery to me until I found out that she had little to no experience in making alcoholic drinks and would simply pour the juice in a large bottle to ferment, leaving the bottle open and unprotected (no airlock or cork).

It’s fine to do this if you intend to drink the wine quite young, but not if you intend to age it.

One by-product of her open fermentation was found at the bottom of the bottles. I always discovered a decent number of dead fruit flies there, which was kind of gross, but it also made sense:

The flies were attracted by the fermenting wine, and I assume that some of them were victims of accidental drowning after a night of heavy drinking.

The Keys to A Good Homemade Vinegar

Seriously, though, it took me a while to figure it out. But right there were two keys for her successful, albeit unintentional, artisanal vinegar-making operation.

The first key was the fact that her elderberry wine fermentation was made from raw juice (European method), meaning there was wild yeast present on the berries.

You’ll recall that Acetobacter, the bacteria responsible for making vinegar, is normally part of the same microbiome as wild yeast. Due to her lack of experience, she also didn’t use enough sugar to end up with a very alcoholic drink, which was perfect for vinegar making.

The second key was revealed to me by accident while I was researching ancestral alcoholic fermentation.

I found out that fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) were also called vinegar flies—not just because they are attracted to vinegar and alcohol but because they often have Acetobacter as part of their gut microbiota and on their body.

That was my eureka moment. In essence, the accidental addition of fruit flies helped the vinegar-making process along.

Finding Your Vinegar Mother

Don’t laugh! My first vinegar mother (a jellylike substance that forms at the top of the alcoholic beverage) was made by infecting some of my mug-wort beer with fruit flies.

I kept the method ultra-simple: I left a jar of beer outside, and in the warm Southern California weather, I had a fruit fly pool party going on within 30 minutes.

An hour later I placed the lid on top, screwed it on quickly, then shook the jar a bit and ended up with around 20 fruit flies in the brew.

In a few hours, once the flies had sunk to the bottom of the jar, I unscrewed the lid and secured a clean paper towel over the top with a rubber band, as the vinegar-making process needs oxygen.

A week later my brew started to smell slightly like vinegar, and within 4 to 5 weeks I had a beautiful vinegar mother on top.

I experimented much more with this method, which I explain later in this chapter. Gross or not, it works quite well.

I didn’t want to include that specific vinegar in any culinary creations due to the dead flies inside, but I used the mother vinegar as a culture starter to “infect” some of my other fermented beverages and turn them into vinegar.

To this date, I still have some vinegars made with that original mother.

But I’m already going too fast here. Let’s slow down and look at the fundamentals first, so we understand what we’re dealing with.

What Is Vinegar?

The answer is super simple: It’s just water and acetic acid.

It’s a natural step in “wild” fermentation.

Vinegar is the theoretical end result whether you do a raw fermentation—such as with the example of my elderberry wine, where wild yeast and Acetobacter are present on the fruit— or you create a wild yeast starter and use it to ferment your wine, beer, mead, or similar alcoholic beverage (see Making a Wild Yeast Starter).

3 Factors Needed to Make Vinegar

Does this conversion of alcohol into vinegar occur all the time? It really depends on several main conditions. You need these 3 factors present to make vinegar:

- The alcoholic liquid should have access to air. Acetobacter thrive in oxygen-rich environments, so a closed container such as a corked bottle is not conducive to vinegar production.

- The temperature in the environment where the vinegar is made should be around 70 to 95°F (21–35°C). The ideal temperature for bacteria growth is between 77 and 85°F (25–30°C). A vinegar fermentation usually takes 3 to 4 weeks at a temperature of around 80°F (26°C).

- For home production, the alcoholic content of the beverage you’re fermenting is best between 5 and 9 percent.

These variables explain why many wild alcoholic ferments don’t turn into vinegar over time, which I guess is a good thing if you didn’t want to make vinegar in the first place.

With all 3 factors present, you can take several approaches to start making your own vinegar.

I always tell my students that their first goal should be to have an active homemade culture; from that foundation, it’s much easier to create more vinegar.

Vinegar Mothers and Active Cultures

An active culture is a raw, unpasteurized vinegar with a mother or live vinegar bacteria (Acetobacter) in it. A vinegar mother is a by-product of the fermentation process.

A mother is composed mostly of cellulose and bacteria, and the presence of this by-product is a good indication that the fermentation process is active.

A mother with a bit of the original unpasteurized vinegar can be used as a starter to create more vinegar. From experience, every mother created will be unique.

I’ve had starters that turned an alcoholic beverage into vinegar quite fast, while others were more sluggish despite the same ambient temperature.

Methods for Making Vinegar From Scratch

I use three main methods to create a batch of homemade vinegar, and thus, my starter for future vinegars:

- Introduce the culture from a friend or a commercial source.

- Create a culture as a natural evolution of the fermentation process.

- Introduce Acetobacter into the alcoholic beverage through a natural source.

Introducing the Culture

The first method consists of obtaining raw vinegar, be it from a commercial source or a friend. The commercial versions are usually advertised as “raw vinegar with the mother.” Very often you won’t see any mother of vinegar in the bottle, but Acetobacter are present.

Obtaining some raw vinegar with a bit of vinegar mother from a friend falls in the same category.

With this living culture, you can use the vinegar as a starter to create more. This method is highly successful if the culture is still alive in the vinegar. I had a couple of failed attempts with a specific batch, and I suspect the failure occurred because the culture inside wasn’t alive anymore.

Creating the Beverage

The second method is a bit more complex because you must create the alcoholic beverage that you’re starting with.

This involves making a wild yeast fermentation with a specific amount of alcohol, then letting it turn naturally into vinegar due to the Acetobacter already present in the liquid.

Failures with this method can occur when the beverage simply doesn’t turn into vinegar, which sometimes is a mystery. But most of the time it will work.

Welcoming Acetobacter

The third method is the crazy one: We “infect” the alcoholic beverage with fruit or vinegar flies on purpose, using the Acetobacter present on the flies as the starter culture.

No need to be all serious about it—this should be viewed as a fun project. The idea is to successfully create your first culture starter at home using one or all three of these methods. From there, it’s much easier to make more, and success is pretty much guaranteed.

Recommended Reads

Recent Articles

Cheese is milk’s destiny. Be inspired by the celebration of milk-in all its forms-especially the transformation of milk into cheese through natural cheesemaking

Read MoreTry your hand at preserving veggies by freezing them! Freezing vegetables is a quick, simple way to preserve them for winter meals.

Read MoreThe possibilities are pretty much endless with wild ingredients — use almost any fresh fruit or juice and a sweetener to create your own custom jam or syrup!

Read MoreDid you know that more than just the seeds of a sunflower are edible? Almost every part of a sunflower are completely safe and delicious when cooked correctly.

Read More

With all 3 factors present, you can take several approaches to start making your own vinegar.

With all 3 factors present, you can take several approaches to start making your own vinegar.